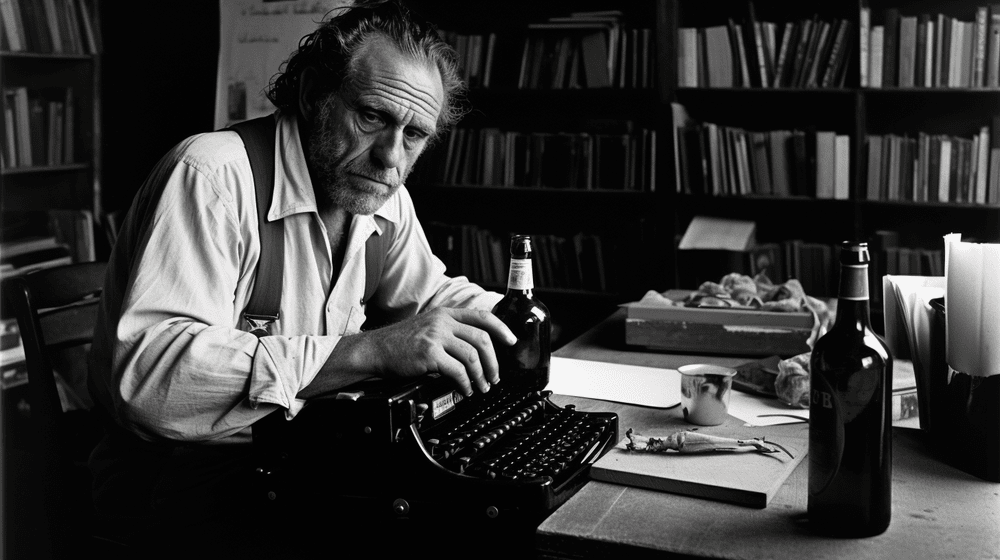

Charles Bukowski on Writing, Creativity, and Living Fully

Reading Time: 10 minutes

In 2023, I dove deep into the world of Charles Bukowski, a poet and novelist known for his works of dirty realism. My interest in Bukowski began when I read Post Office, his first novel about the mundane and crude life he led while working for the USPS.

But it wasn’t until I found Bukowski’s On Writing in a used book store that I became fascinated with this prolific beast of a man. On Writing is a posthumously published collection of letters that Bukowski wrote to publishers, agents, writers, and friends from 1945 to 1993.

Like Van Gogh’s letters to his brother Theo, Bukowki’s letters offer insight into the nature of pursuing a creative path and how this one man navigated the ups and downs of his writing life.

Below, I’ve captured some of the most interesting passages that Bukowski wrote over the years to his friends, enemies, and colleagues. While his language and way of life may be unpalatable to the modern palette, there is no doubt that Bukowski had some valuable and timeless ideas for anyone interested in making their living as an artist.

Rejection and sanity on the writer’s path

“I’ve earned $47 in 20 years of writing and I think that $2 a year (omitting stamps, paper, envelopes, ribbons, divorces and typewriters) entitles one to the special privacy of a special insanity and if I need hold hands with paper gods to promote a little scurvy rhyme, I’ll take the encyst and paradise of rejection.”

Letter to James Boyer December 13, 1959

Separating the art from the artist

“I have often taken the isolationist stand that all that matters is the creation of the poem, the pure art form. What my character is or how many jails I have lounged in, or wards or walls or wassails, how many lonely-heart poetry readings I have dodged is beside the point. A man’s soul or lack of it will be evident with what he can carve upon a white sheet of paper. And if I can see more poetry in the Santa Anita stretch or drunk under the banana tree than in a smoky room of lavender rhyming, that is up to me and only time will judge which climate was proper, not some jackass second-rate editor afraid of a printer’s bill and trying to ham it on subscriptions and coddling contributions.”

Letter to James Boyer May, December 29, 1959

Rewriting creates polished lies

“It’s when you begin to lie to yourself in a poem in order to simply make a poem, that you fail. That is why I do not rework poems but let them go at first sitting, because if I had lied originally there’s no use driving the spikes home, and if I haven’t lied, well hell, there’s nothing to worry about. I can read some poems and just sense how they were shaved and riveted and polished together.”

Letter to Jon Webb, Late January 1961

Good art shakes you alive

“The only thing intelligent about a good art is if it shakes you alive, otherwise it’s hokum.”

“But it’s only when a man gets to the point of a gun in his mouth that he can see the whole world inside of his head. Anything else is conjecture, conjecture and bullshit and pamphlets.”

Letter to Jon Webb, Late January 1961

Failure and playing it loose

“Yes, you’re right: failure is the advantage and I mean the failure of not being held up phonepole high while you’re working with the broad or the poem or the wax statue of Himmler. It’s best to stay loose, work wild and easy and fail any way you want to. Once you polevault 17 feet they want 18 and it ends up you might break your leg trying. The mob must always be dismissed as something as insane as a river full of vomit. Once you put the mob in the wastebasket where is belongs you’ve got a chance to go a good ten and maybe get a split verdict. I do not speak of The Culture of Snobbery which is practiced by many of the rich and the fakirs and rope coilers and electricians and sports writers because they have an idea they have POWER. They are all dependent on the mob like the leaves hanging to the tree branch. What I mean is the kind of dependence that leaves you free to operate widely because you don’t need a kiss on the cheek from the old lady next door, you don’t need praiseology or to lecture before the Armenian Society of Pasadena writers. I mean, fuck that. More paper, more beer, more luck, loose bowels, an occasional piece of ass and good weather, who needs more?”

Letter to Harold Norse, May 12, 1964

“This writing of poetry, we have to play it loose. I’m glad I can work in a little prose and drinking and woman-fighting to break off the sting. I get into those craft interviews sometimes and I feel like those people are polishing mahogany. I suppose it comes from studying too hard and living too little. Hemingway lived hard but got locked in his craft too and after a while his craft became a cage and killed him. I suppose it’s all a matter of feeling your way through.”

Letter to William Packard, October 13, 1972

Avoid rules and write any way you please

“Still it makes me nervous to read those articles on playwriting, ‘a play must have a premise’ and so forth. I am afraid that the problems of our playwrights are the same as everybody else—that is, they are trained, they are TOLD the proper way to do a thing. This may make it go down well, it can help practitioners; it can help bad playwrights become almost good ones, but ‘how to do it’ will never create an Art, it will never shake the old skin, it will never get us out of here. If I were to write a play, I’d write it any damn way I pleased and it would come out all right.”

Letter to Gene Cole, December 1965

You’re a writer if you can write today

“The head must remain where it was. A champ is only as good as his next fight; the last one won’t get him through the first round. Writing is a form of staying alive, a food, a gruel, a drink, a hot fuck. This typer cleans and grinds and stabilizes and prays.”

Letter to Harold Norse, December 1, 1967

“Take some poets. Some start very well. There is a flash, a burning, a gamble in their way of putting it down. A good first or second book, then they seem to dissolve. You look around and they are teaching CREATIVE WRITING at some university. Now they think they know how to WRITE and they are going to tell others how. This is a sickness: They have accepted themselves. It’s unbelievable that they can do this. It’s like some guy coming along and trying to tell me how to fuck because he thinks he fucks good.”

“What I’m trying to say here is that nobody is ever famous or good, that’s yesterday. Maybe you can get famous and good after you’re dead but while you’re alive, if anything counts, then if you can show some magic through the turmoil, it must be today’s or tomorrow’s, what you have done doesn’t count for a shitsack full of cut-off rabbit’s bungholes. This isn’t a rule, it’s a fact. And it’s a fact when I get questions in the mail, I can’t answer them. Or I’d be teaching a course in CREATIVE WRITING.”

Letter to Loss Pequeño Glazier, February 16, 1983

“Talent without durability is a god damned crime. It means they went to the soft trap, it means they believed the praise, it means they settled short. A writer is not a writer because he has written some books. A writer is not a writer because he teaches literature. A writer is only a writer if he can write now, tonight, this minute. We have too many x-writers who type. Books fall from my hand to the floor. They are total crap. I think we have just blown away half a century to the stinking winds.

Letter to the editors of the Colorado North Review, September 15, 1990

Write for survival, not recognition

“Fame + immortality are games for other people. If we’re not recognized when we walk down the street, that’s our luck. So long as the typer works the next time we sit down. My little girl likes me and that’s plenty.”

Letter to Jack Micheline, January 2, 1968

“Writing has saved me from the madhouse, from murder and suicide. I still need it. Now. Tomorrow. Until the last breath.”

Letter to Jack Grapes, October 22, 1992

Bland living leads to bland writing

“You know, the main problem, so far, has been that there has been quite a difference between literature and life, and that those who have been writing literature have not been writing life, and those living life have been excluded from literature.”

Letter to Gerard Dombrowski, January 3, 1969

Find a way to refill the well

“When I say that basically writing is a hard hustle, I don’t mean that it is a bad life, if one can get away with it. It’s the miracle of miracles to make a living by the typer…But writing takes discipline like everything else. The hours go by very fast, and even when I’m not writing, I’m jelling, and that’s why I don’t like people around bringing me a beer and chatting. They cross my sights, get me out of flow. Of course, I can’t sit in front of the typer night and day, so the racetrack is a good place to let the juices FLOW BACK IN. I can understand why Hemingway needed his bull ring—it was a quick action trip to reset his sights.”

Letter to John Martin, November 1970

Teaching is an early, arrogant death

“Oh yes, I must say, anyhow, that it is dangerous for a poet to pose as prophet, a poet/writer to pose as prophet. Here in the U.S. most serious writers write for many years before they are heard from or recognized, if ever. Unfortunately, many damn fools are recognized because their minds are close to the public mind. Generally a writer of force is anywhere from 20 years to 200 years ahead of his generation, so therefore he starves, suicides, goes mad, and is only recognized if portions of his work are somehow found later, much later, in a shoebox or under the mattress of a whorehouse bed, you know.”

Letter to Norman Moser, December 15, 1970

“What I’m getting at, though, is that some of these few who began so well…They teach, they are poets-in-residence. They wear nice clothing. They are calm. But their writing is 4 flat tires and no spare in the trunk and no gas in the tank. NOW THEY TEACH POETRY. THEY TEACH HOW TO WRITE POETRY. Where did they get the idea that they ever knew anything about it? This is the mystery to me. How did they get so wise so fast and so dumb so fast? Where did they go? And why? And what for? Endurance is more important than truth because without endurance there can’t be any truth. And truth means going to the end like you mean it. That way, death itself comes up short when it grabs.”

Letter to William Packard, May 19, 1984

Titles foster or restrict freedom in writing

“Listen, I know what you mean, but Notes of a Human Being is just too precious. Notes of a Dirty Old Man takes the pressure off and allows me to say more.”

“Besides, good and evil, right and wrong keep changing; it’s a climate rather than a law (moral). I’d rather stay with the climates. I think that’s what a lot of revolutionaries fail to see about my work: I’m more revolutionary than they are. It’s only that they’ve been taught too much. The first process of learning or creation is the undoing of teaching. To do this it’s much easier to be a dirty old man than a human being, all right?”

Letter to Robert Head and Darlene Fife, May 23, 1973

Assessing yourself as a writer

“I had an idea I was a pretty good writer but there was no way of knowing, I couldn’t spell and my grammar was crap (they still are) but I felt I was doing something better than they were: I was starving excellently. Because you’re not accepted doesn’t necessarily mean you’re a genius. Maybe you just write badly. I know of some who publish their own books who point to the 2 or 3 examples of great writers of the past who also did that. Ow. They also point to the guys who weren’t recognized in their lifetime (Van Gogh and co.), and that means, of course, that…Ow.

Letter to Mike Golden, November 4, 1980

Writing about childhood

“Ham has been harder and slower than the other novels because where I didn’t have to be careful with the other novels, I have to be careful here. That childhood, growing up stuff has been painful for most of us to do, go through, and there is a tendency to make too much of it. I’ve read very little literature about that stage of life that didn’t make me a little bit sick because of its preciousness. I am trying to luck it into balance, like maybe the horror of the hopelessness can create some slight background laughter, even if it comes from the throat of the devil.”

Letter to Carl Weissner, February 23, 1981

The sounds of the typewriter

“Writing has never been work to me, and even when it comes out badly, I like the action, the sound of the typer, a way to go. And even when I write badly and it comes back, I look at it and I don’t mind too much: I’ve got a chance to improve. There’s the matter of staying with it, tapping away, and it seems to keep mending together; the mistakes and the good luck until it sounds and reads and feels better.”

Letter to John Martin, January 3, 1982

“And when my skeleton rests upon the bottom of the casket, should I have that, nothing will be able to subtract from these splendid nights, sitting here at the machine.”

Letter to William Packard, March 27, 1986

“Yes, the classical composers. I always write with the music on and a bottle of good red. And smoke Mangalore Ganesh beedies. The whirling of the smoke, the banging of the typer and the music. What a way to spit in the face of death and to congratulate it at the same time. Yes.”

Letter to the editors of the Colorado North Review, September 15, 1990

Don’t write to get famous

“When you write only to get famous you shit it away. I don’t want to make rules but if there is one it is: the only writers who write well are those who must write in order not to go mad.”

Letter to Carl Weissner, November 6, 1988

“Read where Henry Miller stopped writing after he became famous. Which probably meant he wrote to become famous. I don’t understand this: there is nothing more magic and beautiful than lines forming across paper. It’s all there is. It’s all there ever was. No reward is greater than the doing. What comes afterwards is more than secondary. I can’t understand any writer who stops writing. It’s like taking your heart out and flushing it away with the turds. I’ll write to my last god damned breath, whether anbody thinks it’s good or not. The end as the beginning. I was meant to be like this. It’s as simple and profound as that.”

Letter to John Martin, July 12, 1991

P.S. If you’re hankering for more Bukowski…

- Watch this short YouTube documentary about Bukowski’s life.

- Check out Bukowski’s best poems, which are more digestible than most poetry.

- Read Ham on Rye, Bukowski’s novel about living an impoverished, lonely childhood in an abusive household during the Great Depression.

- Listen to this podcast about Bukowski’s philosophy on writing and creativity.