A Simple Investing Guide for Growing and Protecting Your Money

Reading Time: 15 minutes

“No wise pilot, no matter how great his talent and experience, fails to use his checklist.” – Charlie Munger

When I turned 18, my mentor gave me $500 and a brokerage account. He said, “I don’t know much about stocks, but you’re smart and will figure it out. Go have fun.”

After watching a Motley Fool video, I bought a few shares of Bank of America and watched my position increase by 11 percent. I was hooked. Once I graduated from college and had some extra cash, I invested significant time in learning about how I could grow and protect my savings.

This investing guide is a working document that codifies everything I’ve learned so far. I created this guide with three goals in mind:

- To define my investing beliefs, principles, and strategy.

- To reduce the probability that I make costly, emotion-driven mistakes.

- To help other people learn more about investing.

I hope this guide helps you on your investing journey. Good luck out there.

As a quick disclaimer, nothing in this document is meant to be financial advice. It’s simply a summary of everything I’ve learned and believe about investing. Many of the ideas were inspired by personal experiences, the memos of Howard Marks, and lessons from Burton Malkiel’s A Random Walk Down Wall Street.

What is investing?

Investing is the process of allocating capital in order to profit from future developments. Because the future is unpredictable, investing is nothing more than a series of bets, which are decisions about an uncertain future. Bets are inherently risky.

While you cannot predict the future with any certainty, you can extrapolate from the past to make informed guesses about the future. To extrapolate intelligently about the past and make rational investing choices, you must develop processes that allow you to make good decisions in the face of uncertainty. A strong decision-making process requires an informed perspective, the mitigation of cognitive biases, and the application of mental models from multiple disciplines.

As an investor, improving the quality of your decisions can increase your chance of good outcomes, but it cannot guarantee them. Nothing can guarantee investing success – there is no action or strategy that will always win.

My investing will focus on investing in equities and bonds. While the principles may apply to other types of investments (e.g., buying a house, building a business, and so on), this guide will focus on investing in financial markets.

Why do I invest?

Primary Investing Purpose (Rational)

I invest to combat inflation and grow the real purchasing power of my money over time. If I invest successfully, I’ll enjoy the most valuable asset money can buy: freedom. Freedom means the ability to do the activities I enjoy, to work for people who I respect, and to help others who I choose to support. With freedom, I will enjoy a higher quality of life.

Secondary Investing Purpose (Emotional)

Investing is fun and exciting. I bought my first stock at the age of 18, and I’ve enjoyed speculating about the market ever since. Investing is also intellectually stimulating – to win at the game of investing, you need to develop an informed perspective, cultivate a rational decision-making process, master your psychology, avoid emotion-driven mistakes, and get lucky. It’s a difficult, but interesting game of chance.

How do I weigh the two purposes?

The majority of my investing activity (~90%) will serve my primary purpose of growing the real purchasing power of my money over time. The remaining 10% of investing activity will fulfill my penchant for speculation.

What are the risks of investing?

“Minimizing downside risk while maximizing the upside is a powerful concept.” – Mohnish Pabrai

Investors face two risks – the risk of losing money and the risk of missing opportunity. While the risk of losing money is discussed more often, both risks are important.

As an investor, you need to position your portfolio to strike the right balance between these two risks. If you’re optimistic about the future of your investments, you will be more offensive. If you are less optimistic, you may choose to be more defensive.

What you buy for your portfolio and how you position yourself over time depends on your beliefs, risk tolerance, and current and future financial needs.

What are the primary investing theories?

There are three basic investing theories – fundamental analysis, technical analysis, and the efficient market hypothesis. All three theories fall short, but they are useful models to understand the behavior of other investors and to build the foundation for your strategy.

Fundamental Analysis/Firm Foundation Theory (“Fundamentalists”)

Fundamental analysis (“fundamentalists”) suggests that a company is worth its intrinsic value, the net present value of its future cash flows. A higher expected growth rate, higher dividend payout, lower degree of risk, and lower level of market interest rates will increase a company’s intrinsic value.

Fundamentalists look to buy companies that are priced below their intrinsic value. The idea is that the market will eventually correct this “mispricing.”

Research suggests that you cannot use fundamental analysis to outperform the market. To assess a company’s intrinsic value, you need to accurately assess a company’s future performance. In an uncertain and fast-changing future, that task is nearly impossible to do on a consistent basis. That said, a few fundamentalist investors like Warren Buffet have done well.

Fundamentalists are typically long-term investors, and they see the market as ~90% rational, ~10% psychological.

Technical Analysis/Castle in the Sky Theory (“Chartists”)

Technical analysis (“chartists”) suggests that you can buy and sell stocks at the right time based on past price movements. Chartists believe that stock prices move in predictable trends. A stock’s value is not about its intrinsic value, but rather how other investors perceive its value. All news about a company is quickly priced in.

The problem with technical analysis is that price movement does not actually tell you information that will allow you to reliably beat the market. Chartists do not accept the randomness of prices because it puts their art in question.

Chartists are typically traders, so they make investments on a short time horizon. Outside of helping you determine a good entry point for a long-term investment, following the chartist theory is not great if you’re looking to make investments with more than a couple month time horizon. Chartists see the market as roughly ~90% psychological, ~10% rational.

Efficient Market Hypothesis

The efficient market hypothesis states that asset prices reflect all available information.

Since all information is already priced in, it’s impossible to buy undervalued stocks and sell inflated stocks. That is, you cannot reliably use fundamental analysis (expert stock selection) or technical analysis (market timing) to outperform the overall market.

If the efficient market hypothesis is true, investors cannot use skill to outperform the markets by capitalizing on mispricings. A rational investor would buy the entire market and hold it.

My take on the 3 investing theories

Fundamental analysis, technical analysis, and the efficient market hypothesis all fall short, but provide useful information for formulating your investing strategy.

Fundamental Analysis

I’m drawn to the value-focused and long-term nature of fundamental analysis. That said, I have two qualms: (1) it’s impossible to appropriately value a company operating in an uncertain world and (2) investor psychology, not value, often drives the market, particularly over short to medium term holding periods.

Technical Analysis

I like the emphasis that technical analysis places on the role of investor psychology. That said, I can’t get behind a model that looks at stock chart price movements and that largely ignores the intrinsic value of a company. The focus on short-term movements also does not align with my desire to be a long-term investor.

Efficient Market Hypothesis

I do not believe the market is always efficient. Rather, in the short-to-medium term, it is driven largely by investor psychology, which can rapidly swing from “everything’s awesome” to “the world is screwed.” In the long run, I do believe the market corrects big irrationalities. I also believe that some markets are more efficient than others, and that when using skill to profit from investing, there is more opportunity in less efficient markets.

Of the three theories, I think the efficient market hypothesis best serves my primary purpose of investing, which is to increase the real purchasing power of my money.

Even though I believe that markets can be extremely irrational, I don’t think you can accurately predict how and when to bet on the irrationalities you observe. A quote comes to mind:

“The market can remain irrational longer than the arbitrager can remain solvent.” – John Maynard Keynes

Identifying irrational behavior is not enough. You have to make the correct bet on that behavior. And making that bet relies on market timing, which you cannot do reliably. I’ve learned this lesson through extremely painful losses in the past, and if I choose to make speculative or market timing bets, it will be with the 10% emotional part of my investing portfolio.

What investing biases must I avoid?

“The investor’s chief problem — even his worst enemy — is likely to be himself.”

To fulfill my primary purpose as an investor, I need to invest rationally. A rational investor maximizes his wealth within the constraints of his individual risk tolerance. I don’t believe investors are rational by nature. That’s part of the impetus of this document – to mitigate the risk that my human defects will lead to irrational investing behavior.

Investors are emotional, driven by greed, gambling, hope, and fear. There are many manifestations of this irrational behavior, which influence market behavior and outcomes:

“The four most dangerous words in investing are: ‘this time it’s different.'” – Sir John Templeton

1. Overconfidence

Most investors overestimate their own skills and underweight the role of chance. They are overconfident in their abilities and over-optimistic about their assessments of the future. They often attribute good outcomes to their own abilities and bad outcomes to external events.

“Listening to uninformed people is worse than having no answers at all.” – Ray Dalio

Lesson: Keep the overconfidence bias in mind when listening to theories or hot stock tips from other investors. Never allow a sense of urgency or fear of missing out to drive an investment decision. If it’s a good investment, it will be there tomorrow.

2. Herd Mentality

The many examples of irrational exuberance in markets highlight how herd mentality can lead to irrational markets. The 1600s tulip craze, Nifty Fifties, 2000s dot com bubble, and cryptocurrency craze are just a few examples to keep in mind. These periods share similar characteristics and patterns – new technologies, business opportunities, or unique valuation criteria that lead to positive feedback loops that drive stock prices very high. Basically, investors find some way to say that “this time is different,” and that leads to a big bubble. Then, a 50-90% crash that burns investors.

Lesson: Don’t get swept up in speculative, get-rich-quick schemes. If it sounds too good to be true, it is. To be a good investor, I must be prudent enough to avoid mistakes, in addition to finding opportunities to bet on. A few easy examples include ignoring the tales of other people making money, IPOs, and “hot tips” from friends.

3. Loss Aversion & Endowment Effect

Losses hurt ~2.5x more than equivalent gains. This bias explains why investors tend to sell the winners and hold on to the losers. Not only do losses hurt, but they tap into the emotions of pride and regret. It hurts to tell friends about losses, while it’s sexy to boast about gains. The endowment effect also causes us to assign excessive value to the investments we currently own.

Lesson: Sell losers when you know. Do not get emotional and “play loose” after experiencing a loss. That leads to making bad or irrational bets that may cost a lot of money. Some investments will not win; in fact, some will lose big. Hold on to the winners. Do not sell a winner just to feel good about yourself.

4. The Falling Knife

When bad news flows about an asset, people do not want to “catch the falling knife.” In some cases, it’s smart to avoid the knife. In other cases, it may be the perfect time to find a good bargain on an asset that is underpriced or that will perform well over the long term.

Lesson: Capitalize on good opportunities when other investors are fearful. You may miss the bottom and suffer short-term losses, but some of these investments have the opportunity to be your greatest bargains (and thus winners) as well.

5. Anchoring

We often anchor ourselves to an initial piece of information or an experience. For example, you may anchor yourself to an investing thesis that proved to be incorrect, to an arbitrary number like the maximum value your portfolio reached, or to the price of a share relative to its trading history. This type of anchoring can influence your investment judgment in irrational ways.

Lesson: Always ask yourself, “Am I anchoring myself to something that is not allowing me to make rational investment decisions?” If yes, find a way to update your thinking so that you can break the unhelpful anchoring cycle.

What is My Investing Portfolio?

The majority of my investment portfolio will follow modern portfolio theory (MPT). Modern portfolio theory holds that diversification in your portfolio can help you generate similar returns with lower risk. The best resource for understanding why MPT is a good strategy is A Random Walk Down Wall Street by Burton Malkiel.

Risk is the variance in the standard deviation of potential returns. Diversification cannot reduce systemic risk (market risk), but it can reduce non-systemic risk (risk of a particular asset). Diversification only works when you have assets that are not perfectly correlated.

The core of my portfolio will be low-cost index funds. I will invest primarily in equities because I like the risk/reward relationship, especially given that I have a 25+ year time horizon. The allocation of my assets may look differently if my personal financial situation changes, or if I have immediate liquidity needs, such as needing to put a down payment on a house.

Differences in my strategy with modern portfolio theory:

- I will invest about 15% of my money in individual stocks. This will keep me more engaged with markets and allow me to bet on specific companies I believe in.

- For the foreseeable future, I will not invest in bonds. I do not like the risk/return profile relative to other asset classes.

- I will make small speculative trades with options from time to time. I will not make a speculative trade if I expect that it will disturb my sleep. No potential financial return is worth losing sleep.

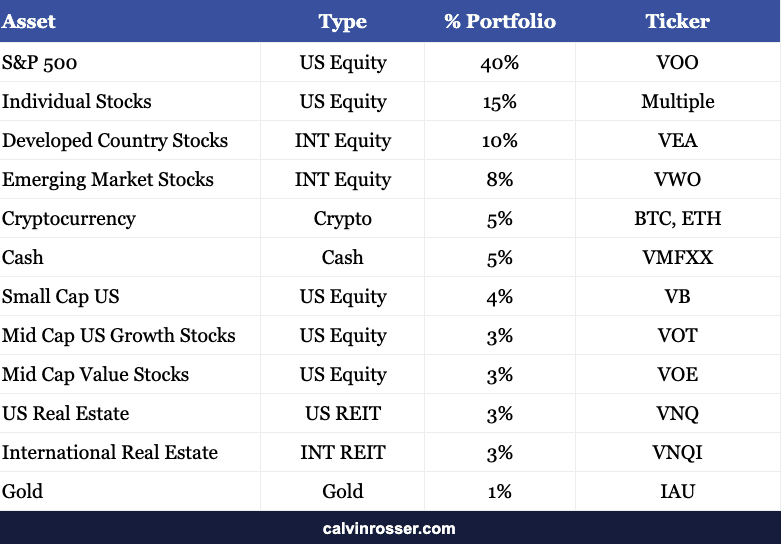

Ideal portfolio allocation:

I will build this portfolio over time with dollar cost averaging. While the jury is still out about dollar cost averaging as it relates to influencing returns, it is a sensible way to mitigate the psychological risk of investing your capital before a large downturn.

I will evaluate and rebalance my portfolio quarterly. I will also do light tax loss harvesting if a large enough market drop occurs.

In more volatile periods or particularly hot markets, I may keep a larger percentage of cash on hand to buy dips in companies or markets. This means that I’m putting myself at risk for missing opportunities that may never return, but it can also be helpful to be more defensive at times. My cash position may also be larger if I don’t have a stable income or if I have unpredictable cash needs.

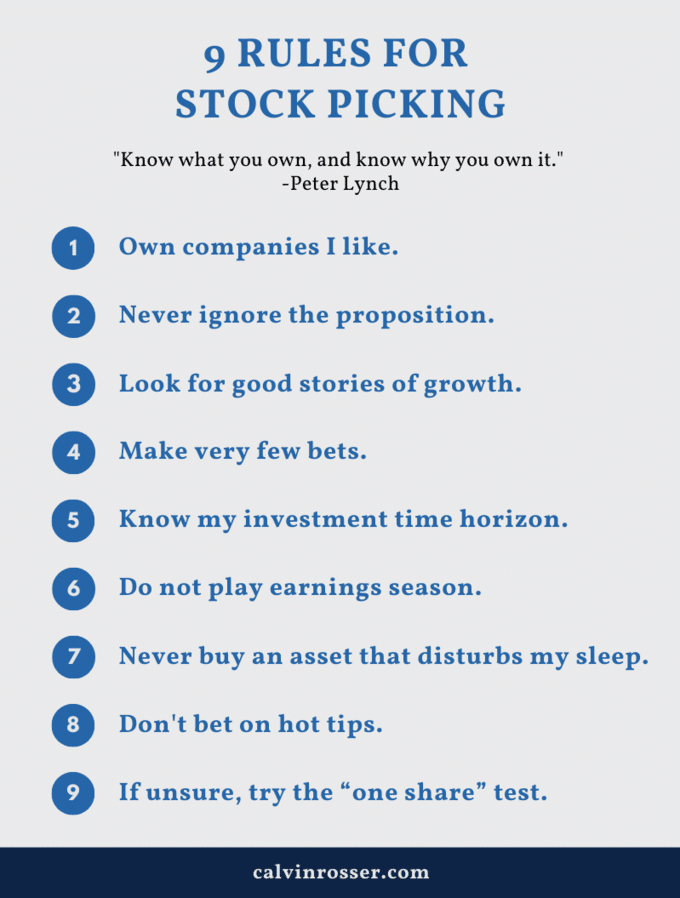

What are my rules for stock picking?

“Know what you own, and know why you own it.” – Peter Lynch

Ten to fifteen percent of my portfolio will be individual stocks. Here are some rules:

1. Own companies I like.

Stock is ownership in a company. If you own companies that you like, you’re more likely to be interested in the company and to stick with the company over the long run. This helps to mitigate the rollercoaster of price performance that typically comes with a single company. If you buy a company you don’t like simply because the price is low, you’re more likely to hate yourself when it goes down further.

2. Never ignore the proposition

Picking winning companies is not enough. An investment’s attractiveness is a function of the price of the asset, the ratio of the potential payoff to the amount risked, and the perceived chances of winning versus losing. Don’t pick “winners,” but ignore the proposition. The goal is to find situations where you like the odds on one side of the other – underdog or favorite.

3. Look for good stories of growth

Look for companies with stories of growth that investors can rally behind. These stories will help propel certain companies higher. It’s important to find the story before other investors do, and always make sure that the story rests on a reasonably strong foundation of value. Also, look for companies with strong moats (e.g. Facebook and Google). If you feel “late to the party,” for a particular investment, consider that companies with strong stories, moats, fundamentals, and management can increase in price for a long time. They can also decrease in price.

“The wise ones bet heavily when the world offers them that opportunity. They bet big when they have the odds. And the rest of the time, they don’t. It’s just that simple.” – Charlie Munger

4. Make very few bets

Only play the game when the odds are in your favor. If you’re reasonably sure this is the case, bet big. If you’re not, don’t bet at all. Remember that playing the game all the time almost always leads to losing. Bet on the quality of the business, not on the quality of management.

5. Know my time horizon before making the investment

How long am I willing to hold a company? Am I capitalizing on a short-term potential mispricing, or am I investing in a company that I’m comfortable for holding for 10 years? Knowing my time horizon will allow me to make bets and be comfortable with the rockiness of outcomes.

6. Do not play earnings season

While you can make money by trading in and out of stocks during earning season, this is not where I should dedicate my energy. This is gambling in a domain outside of my circle of competence, so while I may win from time to time, it’s unlikely I win over the long run.

7. Never buy an asset that will disturb my sleep

Buying 3x shorts of the S&P 500, short-term options, or other speculative instruments have a high likelihood of disturbing my sleep. Unless I’m fully comfortable with the upside or downside of such speculative plays, I will not buy these assets.

8. Avoid betting on hot tips or speculative companies

Do not get swept up by friends or other people who have found an amazing stock that is about to take off.

9. If unsure, try the “one share” test

If I don’t know if I want to make a bet, start small by buying one share of the company. See how I feel holding the stock. That feeling will reveal how I actually feel about owning the company.

What concepts should I keep in mind while investing?

Good investing decisions ≠ good investing outcomes

You can’t evaluate the quality of a decision based on the outcome. Well-thought-out decisions may fail, and poor decisions may succeed. You may be missing relevant information, or luck and randomness may not go your way. So don’t equate good outcomes with good decisions – instead, develop processes that lead to good judgment. From time to time, even those decisions made with good judgment will turn out to be unsuccessful. Find the joy in living with these unsuccessful outcomes. If you aren’t wrong because things didn’t turn out well, you also aren’t right when they do.

You cannot time the market

You cannot say whether stocks will decline or increase in the coming days, weeks, or months. It’s a bad and unanswerable line of questioning. Rather, you should ask yourself about the relationship between prices and value. Are assets overpriced, fairly valued, or underpriced relative to value? When you find a good value (good relationship between price and intrinsic value), buy. If the asset declines further, buy more.

Stay within your circle of competence

Know where you have an edge, and stay within that arena. If you go too far outside of it, you won’t be very successful.

Look for the right balance between offense and defense

Investors face two risks every day – the risk of losing money and the risk of missing opportunity. How you allocate your capital (i.e., portfolio positioning) depends on how you relate to these risks. Good investors do not look for the perfect allocation of assets – they look to strike the appropriate balance between offense and defense to mitigate the two risks of investing.

Looking for a “bottom” is irrational

In downturns, the bottom is reached only when optimism is nowhere to be found. Because the bottom is the day before the recovery begins, it’s impossible to know ahead of time when the bottom has been reached. Instead of looking for the bottom, continue to assess the relationship between price and value. The emotional selling of other investors may lead to great bargains. Instead of looking to make a few perfect buys, make a larger number of good buys. To only invest at the bottom and sell at the top would be paralyzing.

Dollar-cost averaging can mitigate psychological regret

While there is a mixed bag of evidence about whether dollar-cost averaging increases or decreases returns over time, it helps reduce the psychological regret of investing timing and decisions. Especially in uncertain times, it’s worth averaging into a position. Otherwise, I risk doing what happened in March of 2020, which is to remove my entire position at a suboptimal time. When investing in volatile times, decide how much you want to invest by the time you hit the bottom. Spend part of it today, and spend more as the future unfolds. You’ll hedge your probability of being wrong. It’s the way of life for people who do not know what the future holds.

Good/Bad News → Improvement/Decline in Psychology → Price Increase/Decrease

Market reactions are a function of economics and emotion. Good or bad news by itself does not lead to price increases or decreases. What determines the price adjustment is how investors respond to good or bad news. When this happens, you need to assess whether this price adjustment is appropriate, inadequate, or excessive. Based on that assessment, you buy, sell, hold, or do nothing. Investors often swing from “things are flawless” to “things are hopeless.”

Financial market ≠ economy.

Financial markets do not represent the state of the real economy. In general, the real economy lags the financial economy, which is forward looking. Because of this, you will find periods throughout history where financial markets perform well even in poor economic climates. You will also find times where financial markets perform poorly in great economic climates. Do not confuse the market with being a representation of the market.

I hope you enjoyed this guide. Please let me know what you thought, including any feedback you have on how to improve the guide by emailing me at [email protected].

Please also share this guide with any of the people in your circle who may benefit from it. My goal is to help as many people as possible on their financial journey.

Finally, if you enjoyed this guide and want to receive my latest work, subscribe to my weekly newsletter, Life Reimagined, in the big box below.

PS: Come join the conversation on Twitter.

PSS. If you’d like to see me create more stuff, you can support my work here.