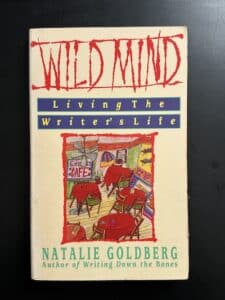

Wild Mind: Living the Writer’s Life by Natalie Goldberg

Reading Time: 9 minutes

Summary

There are many books about writing, but Wild Mind is one of the few worth reading. Using her experience as a writer and wisdom as a Zen practitioner, Natalie Goldberg provides a wealth of knowledge, encouragement, and simple exercises that will enliven your writing life. To get the most out of the book, take the time to do some of the 30+ short exercises she shares.

Get book on Amazon (Must read)

Key Takeaways

Writing practice

“Writing practice allows us to accept, connect with and write from first thoughts.”

Trusting your own mind is an essential part of becoming a writer. Writing practice is a lifelong practice that helps you cultivate this trust in your mind, and it has a few rules. These rules serve as the foundation of the writing practice exercises Goldberg suggests and can extend to your other work.

- Keep your hand moving. When you sit down to write, whether it’s for ten minutes or an hour, once you begin, don’t stop. If an atom bomb drops at your feet eight minutes after you have begun and you were going to write for ten minutes, don’t budge. You’ll go out writing.

- Lose control. Say what you want to say. Don’t worry if it’s correct, polite, appropriate. Just let it rip.

- Be specific. Not car, but Cadillac. Not fruit, but apple. Not bird, but wren. Not a codependent, neurotic man, but Harry, who runs to open the refrigerator for his wife, thinking she wants an apple, when she is headed for the gas stove to light her cigarette.

- Don’t think. We usually live in the realm of second or third thoughts, thoughts on thoughts, rather than in the realm of first thoughts, the real way we flash on something. Stay with the first flash. Writing practice will help you contact first thoughts. Just practice and forget everything else.

- Don’t worry about punctuation, spelling, or grammar.

- You are free to write the worst junk in America.

- Go for the jugular. If something scary comes up, go for it. That’s where the energy is. Otherwise, you’ll spend all your time writing around whatever makes you nervous. It will probably be abstract, bland writing because you’re avoiding the truth. Hemingway said, “Write hard and clear about what hurts.” Don’t avoid it. It has all the energy. Don’t worry, no one ever died of it. You might cry or laugh, but not die.

Style

“Style requires digesting who we are. It comes from the inside. It does not mean I write like Flannery O’Connor or Willa Cather, but that I have fully digested their work, and on top of this or with this I have also fully digested my life: Jewish, American, Buddhist woman in the twentieth century with a grandmother who owned a poultry market, a father who owned a bar, a mother who worked in the cosmetics department of Macy’s—all the things that make me. Then what I write will be imbued with me, will have my style.”

Journaling vs. writing practice

Journaling has a fascination with the self, emotions, and situation. Writing practice includes these things but tries to move beyond them by loosening your attachment to what is happening and your thoughts about it.

The idea of writing practice is to get to the true nature of your mind. You want to get to the place that generates thoughts and eliminates the sense of self that preoccupies most journal entries.

Writing is elemental

“Writing is elemental. Once you have tasted its essential life, you cannot turn from it without some deep denial and depression. It would be like turning from water. Water is in your blood. You cannot go without it.”

Real writing comes from the whole body. It requires you to be where you are, to escape the monkey mind of your existence. A walking meditation, or paying attention to something mundane about what you’re doing can drop you into this space.

Getting stuck

“In writing practice, sometimes you just go along writing, boring yourself, treading water, not really saying anything. You know it, but you don’t know how to break through. A helpful technique: right in the middle of saying nothing, right in the middle of a sentence, put a dash and write, “What I really want to say is…” and go on writing.”

Doing this allows you to make a hard pivot toward what you really want to say.

When you’re struggling with the discipline to write, call a friend and make a date to meet them at a cafe or a restaurant to write together. Even if they can’t come, show up and pretend like they are coming. This little trick will get you writing more.

Reading aloud

“It is important to read aloud what you write. In writing groups, I ask people to write and then immediately afterward ask them to read it to either the large group, a smaller group, or a person sitting next to them. It is part of the writing process, like bending down to touch your toes and then standing up again. Write, read, write, read. You become less attached to whether it is good or bad.”

Do nothing

Spend one day a month doing nothing. The whole day. Just lie around. No cooking, jogging, reading, brushing your teeth, or anything. If you feel like it, write at the end of the day. If not, this lazy day can fuel your writing for a long time. Just be lazy and see how it goes.

Just write

“No one cares that much whether you write or not. You just have to do it.”

Give yourself permission to fail

“It was important to give myself permission to fail. It is the only way to write. We can’t live up to anyone’s high standards, including our own.”

Exercises

Below are some of the 30+ exercises that Goldberg provides to help you train your mind as a writer, build confidence, overcome blocks, develop an eye for original detail, and discover the joy of integrating writing your life. For each exercise, remember the rules of writing practice.

10-minute timed writing

- Begin it with “I remember” and keep going. Every time you get stuck and feel you have nothing to say, write, “I remember” again and keep going. To begin with “I remember” does not mean you have to write only about your past.

- Now go for another ten minutes. This time, begin with “I don’t remember” and keep going. This is good. It gets to the underbelly of your mind, the blank, dark spaces of your thoughts.

- Using the negative, “I don’t remember,” allows us to make a U-turn and see how things look in the night. What are the things you don’t care to remember, have repressed, but remember underneath all the same?

- Now try “I’m thinking of” for ten minutes. Then, “I’m not thinking of” for ten minutes. Write, beginning with “I know,” then “I don’t know,” for ten minutes. The list is endless: “I am, I’m not”; “I want, I don’t want”; “I feel, I don’t feel.”

One sentence at a time

Pick a sentence that comes to you, a little idea you believe. Something like “I fell in love with my life one Tuesday in August.” Then write the next line and the next one and the next one. Don’t think ahead. Just build the story, one sentence after another. Don’t overthink it.

Slowing down

Pick a subject, situation, or story that is hard for you to talk about. Write about it in a slow, even, and measured way. Don’t skip over anything. It may take you several days or a month to finish, but keep going until it is. Include the colors, smells, and the time of day.

Before you start writing, try taking a drink of water or a walk around the block. Do something to ground yourself so that you can write from that quiet place of equanimity and truth.

10 days of writing practice and reflection

Write every day for ten days in a row. Don’t read that writing until two weeks later. Then sit down and re-read what you’ve written. Underline sentences that stand out. Put parentheses around sections you like. Develop those ideas by re-entering that same topic via another timed writing.

Every week for a full month, make a writing schedule and stick to it. Be realistic about what you can do and see how it goes. Meet up with other writers if it’s helpful.

Make a writing schedule

Make a writing schedule at the beginning of the week. You can write every day, only on Tuesday, or for 30 minutes after work. Just pick something you can do. Then stick to it. Do this every week for a month, and look back at the end to see what you produced.

What you want to write about

Instead of daydreaming about writing, write for 15 minutes about “I want to write about” and be very concrete about what that is, avoiding fluffy words or empty platitudes. You can write about the details of the story you want to tell, and if you get stuck, spend 10 minutes answering “I don’t want to write about” and see if that merits inclusion in your story.

You can also use this frame to write about topics that you are interested in, but that may not have manifested in your writing. Try topics like painting (or a hobby you enjoy), politics, people you’ve known, animals, cars, summer, places you’ve never been, games, meals, and cafes.

Create a running list of topics that you may want to write about. Return to that list and know that when you return to it you will not want to write about anything on the list. Pick something, and shut up and write.

Summer vacation

Write about what you did during various summers in detail. Not just what you did, but slow, vivid descriptions of everything that you felt and experienced. Just pick one summer you remember from childhood and stay with it, remembering to include specific, original details.

Try oral writing

Spend time with a friend or alone, and speak for 10 minutes about what you remember. This is oral writing. You can use a different prompt. Just try to shortcircuit the critic of writing and speak freely. This may help you jumpstart the engine.

Be kind to yourself

It’s easy to be critical, to think about all the ways you are falling short as a writer. Try doing a timed writing where you honor the sweetheart within you. Write about all the kind things you can say about yourself and your writing. If you can’t do it from your own voice, pick a friend, family member, or stranger who offers you kindness and compassion.

Write about untouched areas

- Write about what disturbs you: what you fear, and what you have not been willing to speak about. Don’t worry about other people reading it. They won’t. Just go and see what happens.

- Write about sleep. Write about your sleeping patterns, sleepless nights, dreaming, taking naps, what it feels like to sleep next to someone else, beds you’ve slept in, sleeping in new countries, tricks you have to sleep, and so on. See what emerges.

- Write about the place where you grew up. Include the original details of home life. Don’t be sentimental. If it helps, write from the perspective of your mother, dog, or aunt.

- Write about a discipline you know well. It could be about cooking, running, surfing, painting, or anything you know. You can use this as a warmup to get into a flow state.

- Write about everything you know about dying. You can write about near-death experiences, about watching other people die, about what you’ve read. It doesn’t matter.

- Write about the things you will miss when you die. Be specific. Include silly things that only you care about.

- Write about a spiritual experience. It could be a time you felt a God-like presence, when you felt larger than life, or when you felt very connected.

- Write about something you really loved. This could be an experience where you felt whole and complete in an activity all for itself. It could be silly or profound. Include the small details about the experience.

- Make a list of what pleases you. Then do a timed writing about one of the items on the list. Focus on what really pleases you, not what other people like about you.

- Write about something silly you do. Kiss a tree or put an apple in your mouth and walk around. See that you can write even about silly things.

Using experiences to write

Take a bite of a food you like. Write down a strong word about it. Not tasty, salty, good, but tiger, muscle, glass. The word does not have to make sense.

You can do a similar exercise by smelling flowers outside or paying attention to how you feel when you do ordinary daily tasks. Get in touch with the emotions behind the experience, what they’re really like. These exercises will teach you how to make vivid, good, and unique comparisons.

Write about travels

Write about towns and cities you have passed through and places you stayed in a week or less. Write about a car trip. Write about trains, planes, and hotels. Make up travel topics and explore unexamined topics. Do timed writing exercises around each of these topics.

“I am a writer“

Before bed and when you wake up, say to yourself: “I am a writer.” Even if you don’t believe it, just plant the seed. Say it when people ask what you do, even if you feel like a fool.

Contact another writer

Reach out to a writer you know about. If they live near you, say you’d like to take them to lunch. Or go to a workshop the writer is teaching. Or just meet up with other fellow writers. It’s important to be around other people who love writing. It confirms your writing life. Find a way to do it.

Words you like

Write down and keep a list of words you like. Read the list to a friend or read it aloud before you begin writing. You’re getting in touch with the words. You can even do this for uninteresting, everyday words. These exercises connect you with the power of every word.

Train your mind for original details

Look around and take five minutes to describe where you’re sitting. Don’t say “a lovely doily on top of a well-made table.” “Lovely” and “well-made” are your opinions. Stick to original details. “They’re a white doily on top of a red Formica table. A woman in knee-high socks just walked by. She has a mole on her upper lip and the tip of her long braid brushes her leather belt.”

Make a list of things you fear and use them in a timed writing about what you love. This can intensify how you speak about what you love as you’re juxtaposing it with what you fear.

Moving beyond abstractions

“You have to earn the right to make an abstract statement.”

That right is earned by using original detail. It’s much more powerful to say “Life sucks” after you’ve built a vivid scene than to simply say “life sucks” and move on without explanation.

To train this muscle, start with five simple abstractions, then write a paragraph for each with solid, concrete details. You can reverse the exercise as well. Start with a description, then use an abstraction.

Assert Yourself

Don’t worry too much about explaining yourself or appearing overly logical. Don’t get bogged down in the need to explain. Just state what you want to say fearlessly. Avoid the pull to say “because” and to elaborate on everything you want to say in such a logical way.

🙈 That's all for now! If you enjoyed this piece...

📚 If you want to discover more great books...

Explore the best books for expanding your mind, the best self-help books, the best philosophy books for beginners, books for people who don't enjoy reading, and more great books.

You might also enjoy these book notes...

- On Writing Well: The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction by William Zinsser

- The Creative Act: A Way of Being by Rick Rubin: Summary & Notes

- Do the Work by Steven Pressfield

- Turning Pro by Steven Pressfield

- Creativity, Inc.: Overcoming the Unseen Forces That Stand in the Way of True Inspiration by Ed Catmull

- Reinvent Yourself by James Altucher

- Tribes: We Need You to Lead Us by Seth Godin

- The War of Art by Steven Pressfield

- Show Your Work! by Austin Kleon